EEB Undergrad Nicole Regimbal's study reveals frog species most at risk from motor vehicles in Southern Ontario

Anyone who’s played the video game Frogger knows that roads can spell the end for digital amphibians.

The real world is no less treacherous as a million amphibians, reptiles, mammals and birds are killed by motor vehicles on GTA roadways every year. The toll is so great that road fatalities are the second greatest threat — behind only habitat loss — to many at-risk species in the province.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise since, according to a report from the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA), major roadways in southern Ontario grew from some 7,000 to 36,000 kilometres between 1940 and 2000.

But now, new data analysis by a group of conservation biologists could give the most vulnerable frogs a safe way to get to the other side.

Nicole Regimbal, a fourth-year undergraduate student and member of University College, is completing a double major in ecology & evolutionary biology and environmental ethics.

Regimbal recently analyzed amphibian population and mortality data for 23 locations throughout the GTA. The sites were selected because each included a roadway and habitat that supported populations of amphibians.

“We wanted to see whether the species present in the area were the same as the species that were experiencing mortality,” says Regimbal.

She found that in two study areas in the Rouge River watershed north of Toronto, four of nine frog species had disproportionately higher mortality rates: the American Toad, Green Frog, Grey Treefrog and Northern Leopard Frog.

Generally, frogs are vulnerable because they’re slow moving; they cross roads frequently to travel from one habitat to another; and being cold-blooded, they’re attracted to the warmth of roads.

American Toads are particularly vulnerable, likely because they travel long distances at night during their relatively extended breeding season. The Green Frog takes long treks during migration. The Northern Leopard Frog has developed little avoidance behaviour, even in the face of approaching motor vehicles. And the Grey Treefrog is an especially active and itinerant species.

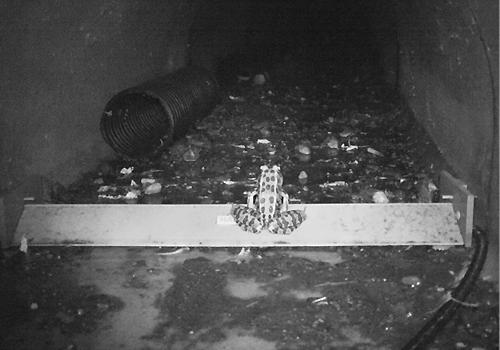

A potential solution to the threat already exists in regions like the Heart Lake Conservation area in the Etobicoke Creek watershed. Three tunnels or eco-passages passing under roadways provide amphibians with a safe, subterranean route. They are especially effective in combination with fences that prevent frogs from crossing roads and divert them into the tunnels.

Regimbal’s collaborators on the project were Jonathan Ruppert, an adjunct professor in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology (EEB) and a senior research scientist with the TRCA; and Andrew Chin, a research analyst with EEB and TRCA.

The TRCA is one of 36 conservation authorities in Ontario mandated to protect natural environments. It oversees a region that comprises nine watersheds and stretches from Ajax to Mississauga, and from Lake Ontario to Dufferin County.

According to Ruppert, the new analysis will aid in making decisions about the construction of new eco-passages where they are most needed.

“It definitely will,” he says. “It’s our first big case study within our jurisdiction to show that species are using them — and not just reptiles and amphibians, but mammals as well.”

After she graduates in the spring, Regimbal will enter the ecology & evolutionary biology graduate program at U of T and plans to study the relationship between global change, the movement of organisms and conservation.

“The study on frog mortality was very fulfilling and personally solidified my desire to pursue a career in research,” says Regimbal.

“I sometimes find myself overwhelmed by the magnitude of the problems we face. But this work felt meaningful as a first step to implementing measures that can have very positive impacts. It was comforting to feel like I contributed to making a positive mark on the world — regardless of the scale. I’m excited to do more!”